Have you noticed that a box of crackers is costing a whole lot more these days than it used to?–especially if you’re wanting specialized grains or herbed flavors? Why not “save” and make my own? Right! I’ve had a hankering for cracker flavors you just can’t find at the grocery, a lust for crackers made with our super-nutritious Southwest flours and herbs. So…fortified with locally-sourced materials, I searched cracker recipes to guide me, but I batted almost zero–so few recipes are out there. I took this dearth as a challenge. Tia Marta here to share some of my cracker experiments–and to challenge YOU to invent your own holiday crackers!

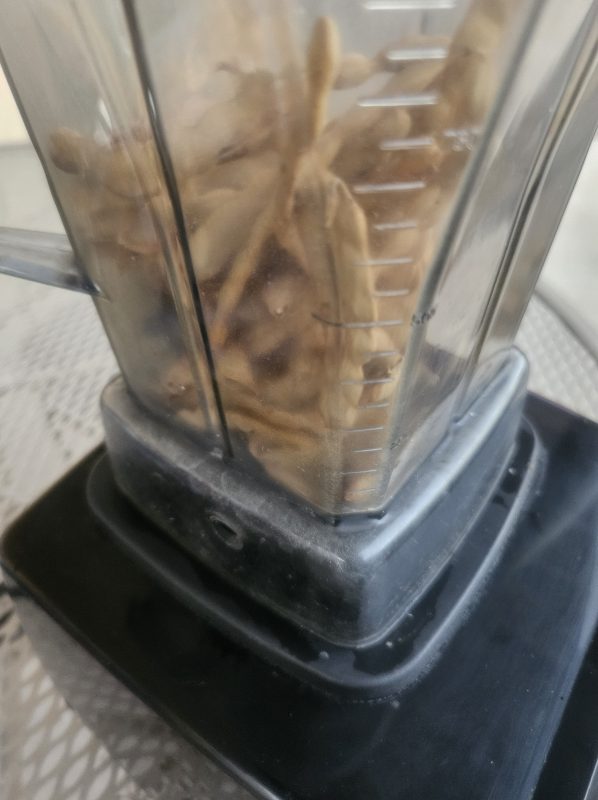

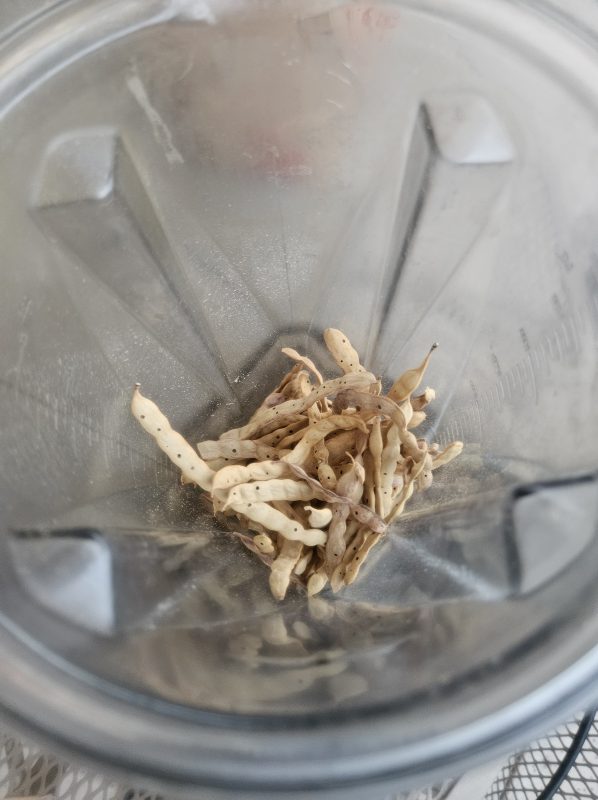

This is fun new territory. First with the goal of a gluten-free Southwest cracker, I took on Native blue cornmeal as the major delicious ingredient, with tapioca flour and chia seed as “binders”.

Recipe for Gluten-free BlueCorn-Amaranth-Chia Crackers:

Ingredients:

3/4 Cup blue corn meal (available from NativeSeedsSEARCH)

3/4 Cup tapioca flour

1/2 Cup amaranth flour

1/2 tsp baking soda

1/2 tsp sea salt (I used salt from Baja California)

2 Tbsp non-fat plain yogurt (Greek yogurt can be a no-fat substitute for butter)

3/4 Cup lowfat buttermilk

1 Tbsp. chia seed

1 Tbsp mesquite honey (optional, amaranth flour can be a little bitter) (or a generous glob of honey on a teaspoon)

You’ll need a greased pizza pan and a greased rolling pin.

Place half the dough in center of a greased pizza pan. With your fingers press the dough down and outward. Your goal is to create a thin 1/8″ layer of dough on the pan. Using a greased rolling pin, flatten the dough out from the center. Use fingers to push the the thinnest edges back to a uniform thickness, or edges will scorch in the baking. Carefully cut the thinned dough with a sharp knife into squares, and make holes with a fork to even the heat. Bake 8-10 minutes or until you see a toastiness. With a metal spatula, lift the hot crackers off the pan right away to cool.

Enjoy nutritious gluten-free BlueCorn-Amaranth crackers with thin slices of membrillo, or with a creamy cheese–a new taste treat with a hint of sweetness.

You’ll see more pictures of the cracker dough prep-process below.

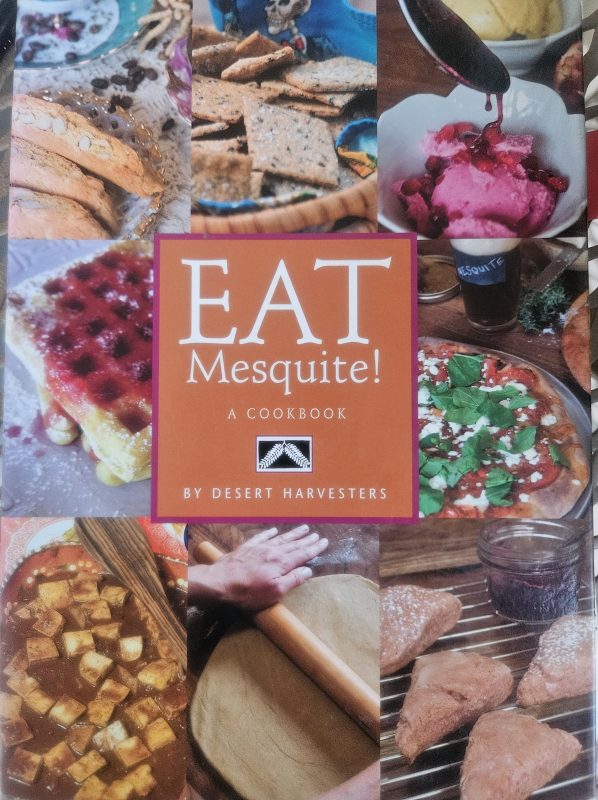

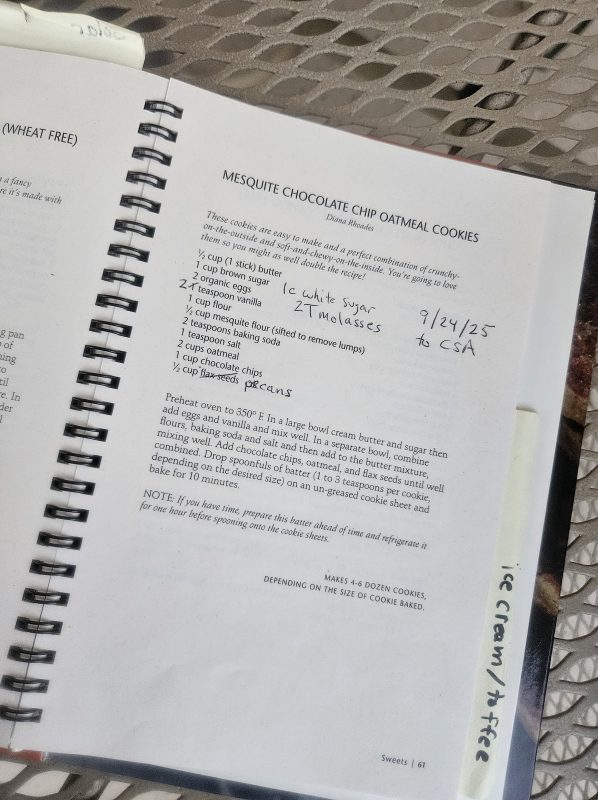

Inspired by rosemary-flavored flatbreads, I decided to try making a rosemary mesquite cracker with local heirloom wheat. Our garden supplied the fresh rosemary to cut into edible bits…. This local combination came out great:

Recipe: ROSEMARY-MESQUITE-PIMACLUB WHEAT Crackers

Ingredients:

3/4 Cup barley flour

1/2 Cup Pima Club wheat flour (from Ramona Farms, Sacaton, AZ)

1/4 Cup mesquite pod flour (any more than this will become too strong a flavor)

1/2 tsp baking soda

1/2 tsp fine sea salt (I used Sea of Cortez pilgrimage salt crystals collected by a friend)

1/4 Cup oat bran

2 Tbsp non-fat plain yogurt

1/2 to 1 Cup low-fat buttermilk

1/2 tsp glob of mesquite honey (optional)

Optional “topping” suggestions: 1/8 tsp additional, dry, finely chopped rosemary leaf; 1/8 tsp crystallized sea salt; 1/2 tsp barrel cactus seed or saguaro seed; 1/2 tsp popped amaranth seed; 1 Tbsp grated aged cheddar

You’ll need a greased pizza pan or baking sheet, and a greased rolling pin.

Directions (similar to previous recipe):

Preheat oven to 350F. Pre-soak rosemary bits in buttermilk to enhance flavor. Sift together all dry ingredients except the oat bran. Add oat bran separately as it will not pass thru sifter easily. Cut yogurt into dry ingredient mixture. Add buttermilk mixture gradually until dough is firm–not liquidy.

Place half the dough in center of greased pan and roll outwards until very thin and even (approx 1/8″ thickness). Be sure to tuck edges back to be equal thickness as center.

Sprinkle top of thinned dough with your desired topping. Here I’ve used rosemary bits, crystals of sea salt, and a sprinkle of chia. Pat the “topping” into the dough with your fingers so it will stick when baked. For this batch I used a cookie cutter through the rolled dough to make round crackers.

With the other half of the dough I used a greased rectangular pan which confined the rolling pin action to only two directions. Here I formed the dough into a thin circle to make “pie” wedge crackers.

Bake 8-10 minutes and check to see that the crackers have crisped. With metal spatula lift them from pan immediately to cool.

These Rosemary-Mesquite-PimaClub Wheat crackers are savory and pair well with cream cheese and jam, or as a foundation for colorful holiday canapes.

Lots of work goes into making crackers! But if our wonderful local desert grains aren’t available as crackers commercially, this is the only way to go. I challenge you to give them a try–to experiment with your own local grain combos!

Crackers are best made in greater quantity–not piecemeal. I’ve had this vision of an Indigenous-owned and -operated enterprise, with ingredients sourced sustainably from the desert, someday filling this “cracker niche,” making good revenues and providing us all with nutritious, appropriate Southwest-flavored crackers….